From the Archive is your first book. What is the story behind the making of the book?

In early 2009, after being laid off from my day job, I joined Flickr the online photo community, and began uploading photographs I was making with a digital camera for the previous couple of years. For most of the nineties and into the early aughts I hadn’t been very photographically engaged, for many reasons. I was shooting, but it was sporadic and without much intensity. Around 2005 I decided to sell my analog gear, cameras, and darkroom stuff, and go completely digital. After 30-plus years of working in a darkroom, I didn’t have any desire to continue with that, not that there is anything wrong with it I hasten to add, but not for me anymore. So after a couple of years with the digital camera, I wanted to start putting some work out there and Flickr seemed like an interesting way to do it. I didn’t think my early digital stuff was all that good, but, with no job at that point, I had both an opportunity and a need to engage with whoever like-minded photographers I might find out there. And I did, and it was reinvigorating for me. Among other things, I found out there were some others like me who photographed obsessively in the seventies and early eighties, went through some sort of slack period, and reemerged in the internet era. So, later in

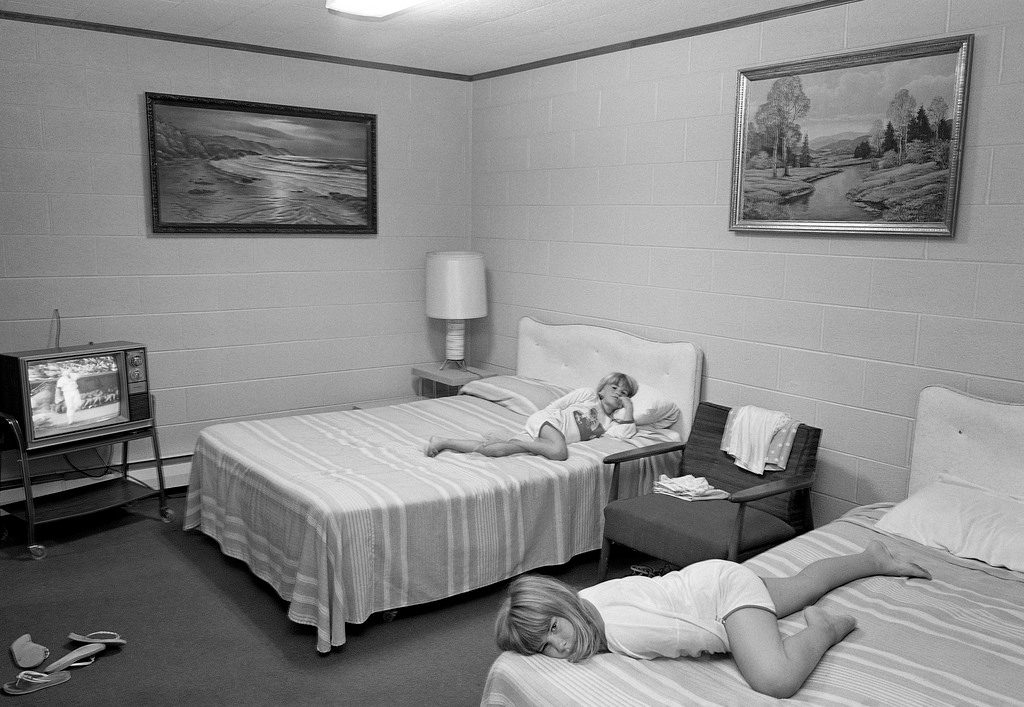

So, later in 2009, I began to post some of my early stuff, interspersed with my current work. It started to get some nice reactions in the online community, but the big bonus for me personally was that I was getting a huge kick out of looking through these old images. The bulk of the work was made when I was in my twenties and early thirties so I was now a generation and a half removed from them, looking with a much different eye. Hard to describe the feeling, but it was at once detached as if looking at another person’s stuff and connected via some kind of time portal. The whole notion of the internet’s ability to obliterate time started to become very personal for me, and I dug into that experience I was having through the second life of these pictures. Some of the images I was posting were shown publically in a few venues around Detroit back in ’79-’81, but, aside from my friends and a few others in the photo community in Detroit, not many eyeballs saw them back then. Winogrand famously talked about allowing a certain amount of time to pass to separate one’s emotions in the act of photographing from evaluating the resulting photograph. Well, even though I was reconnecting at a general level with my younger being, I had almost no recollection of the specific circumstances of most of the images!

It was fascinating to see the markings on the contact sheets from my 20th-century self, but I was re-evaluating these pictures with a 21st-century accumulation of cultural information. A little more than a year passed from the time I started posting these images online when, out of the blue near the end of 2010, I got an email from Maxime and Claire at FP&CF. They wanted to know if I’d like to do a book on my ‘70s –‘80s stuff and attached a picture showing small prints of my Flickr images spread out on a table. I was blown away actually. Here were these two young French publishers, born and raised in the digital era, interested in a body of work made by someone in the last century. I never signed a contract. We executed the project with mutual trust and collaboration. The collaborative experience of the project itself, and honoring the initial reaction to the images by Maxime and Claire, were as important to me as having the book out there. And I can say wholeheartedly that Maxime and Claire were a delight to work with.

How many photographs do you have in your archive and how many of them make the book? Could you give us some details on how you and FP & CF worked on the editing of your photographs to make the book?

I assume you’re speaking of the last-century analog stuff, and I would say something less than 5 figures of negatives. No way was I anyway near the output of a Winogrand or Eggleston! I always had a « regular » job to pay the bills and was essentially a weekend warrior in the photography game. About the book edit, Maxime and Claire proposed an initial edit, based on their response to what I had been posting to Flickr. And as I said, making the book around their enthusiastic reaction to the pictures was the most important thing for me. I wanted the book to be an artifact of our collaboration over the existence of these pictures, and I think that is what they wanted also. Some of the pictures in their initial edit I didn’t think were particularly strong and I said so, suggesting some alternatives. Over about a year and a half, we tweaked the edit. In that period, I was still posting new stuff from the archives too, some of which were incorporated. I thoroughly enjoyed our conversations back and forth during that time, and after about five iterations of the edit, we settled on one that I feel maintained their original impulse.

« My interest was in how the camera gave you something that looked like the truth, and what I wanted to do is place myself and my camera in situations that might allow hidden « truths » to be revealed in the flow of time »

It is historically documenting a period about South Lyon, Detroit, and some other parts of Michigan’s everyday life. Did you have any project to document your area and do you consider From the archive as a documentary photo book?

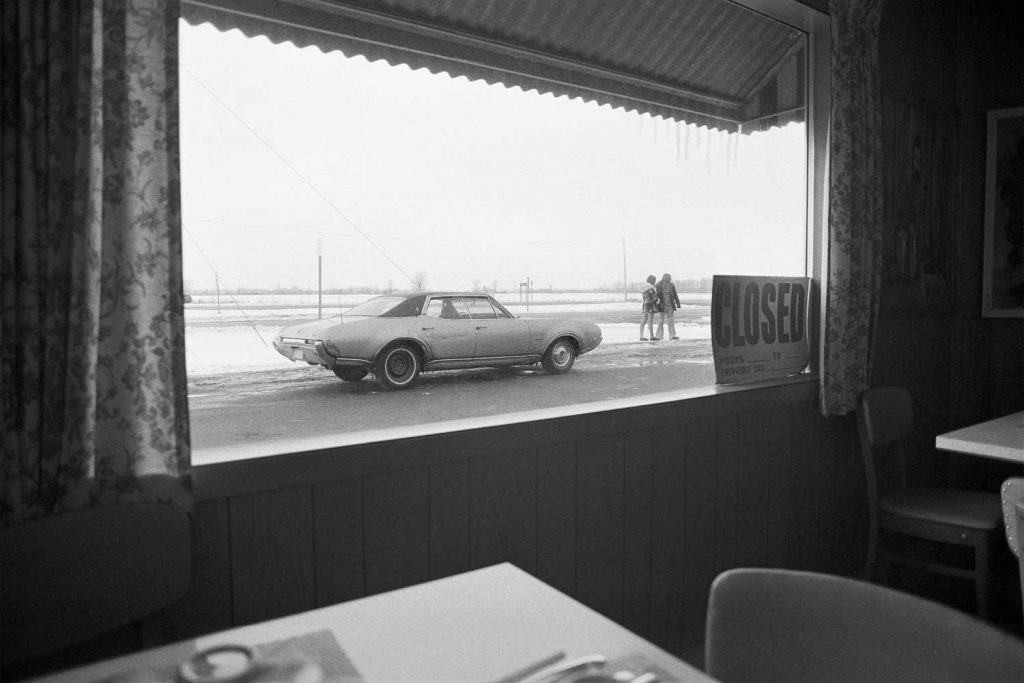

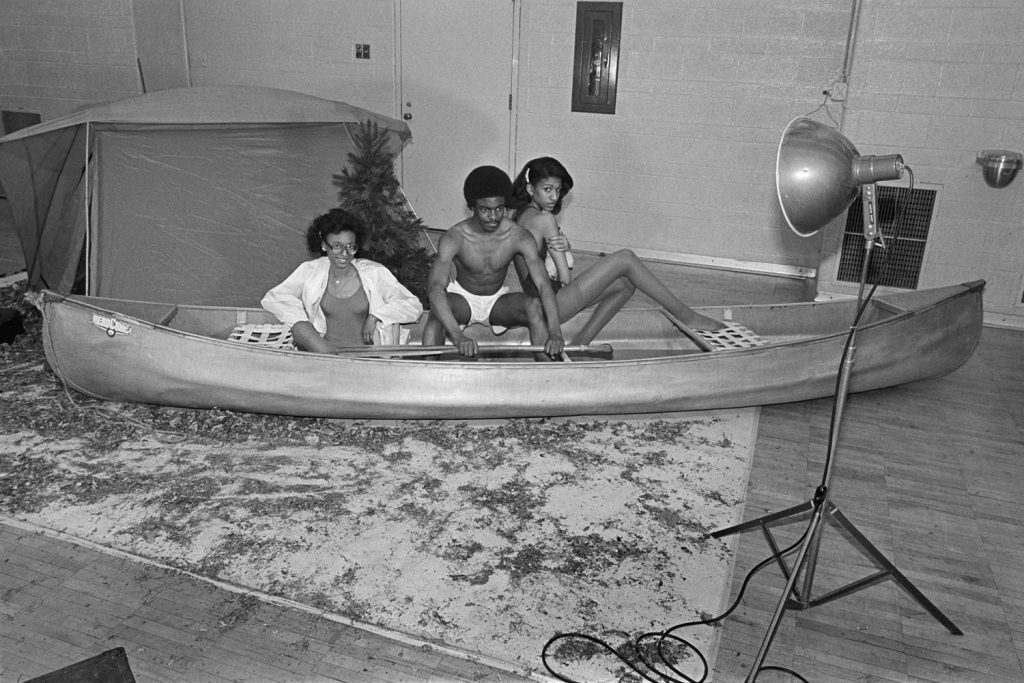

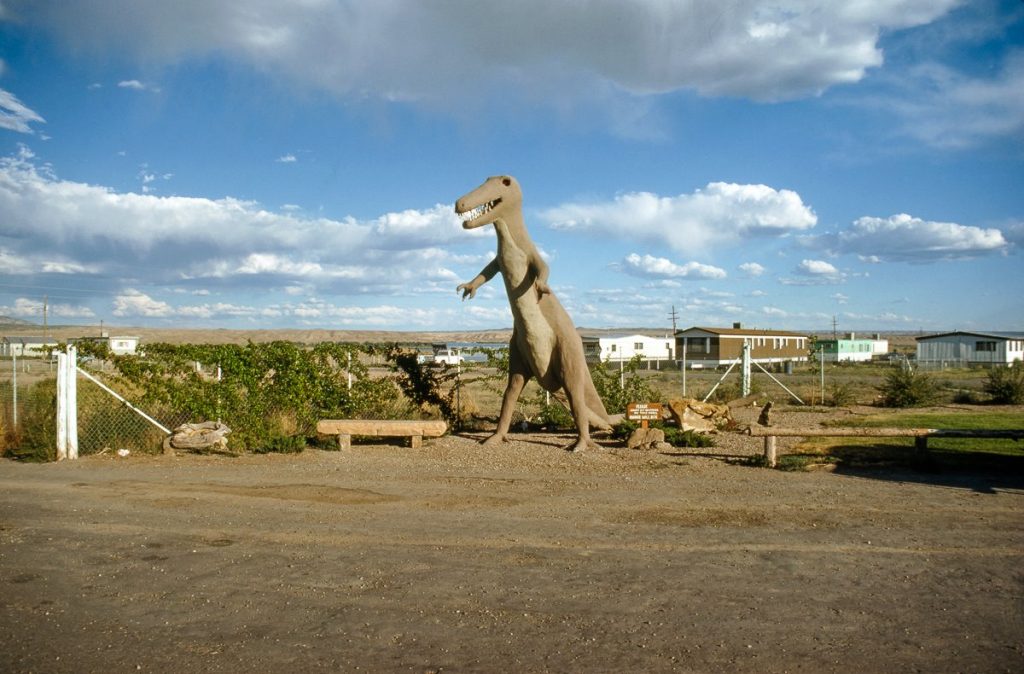

Well, though one could indeed say that I worked in a straight-from-the-camera documentary « style », I never considered myself a documentary photographer in the commonly recognized sense of the term. And I never worked on pre-conceived projects. My interest was in how the camera gave you something that looked like the truth, and what I wanted to do was place myself and my camera in situations that might allow hidden « truths » to be revealed in the flow of time. To me, the photograph was a product of a three-sided collaboration: the self-indulgent me, the camera, and the world before me. If I was documenting anything it was that relationship. I don’t think that is an uncommon impulse among photographers, and over the years the sharing of this language of photographic truths is a big part of the enjoyment of the game for me. I can understand how someone looking at these pictures would see them as a historical document of a time and place – they do look like that! But that is just a by-product of the game I was playing. You can thank the camera and time for that look, but not me! Similarly, I consider the From the Archives book, not as a documentary photo book, but as a document, or artifact, of a relationship between the older me, two young French people, the internet, and a group of pictures made in the last century.

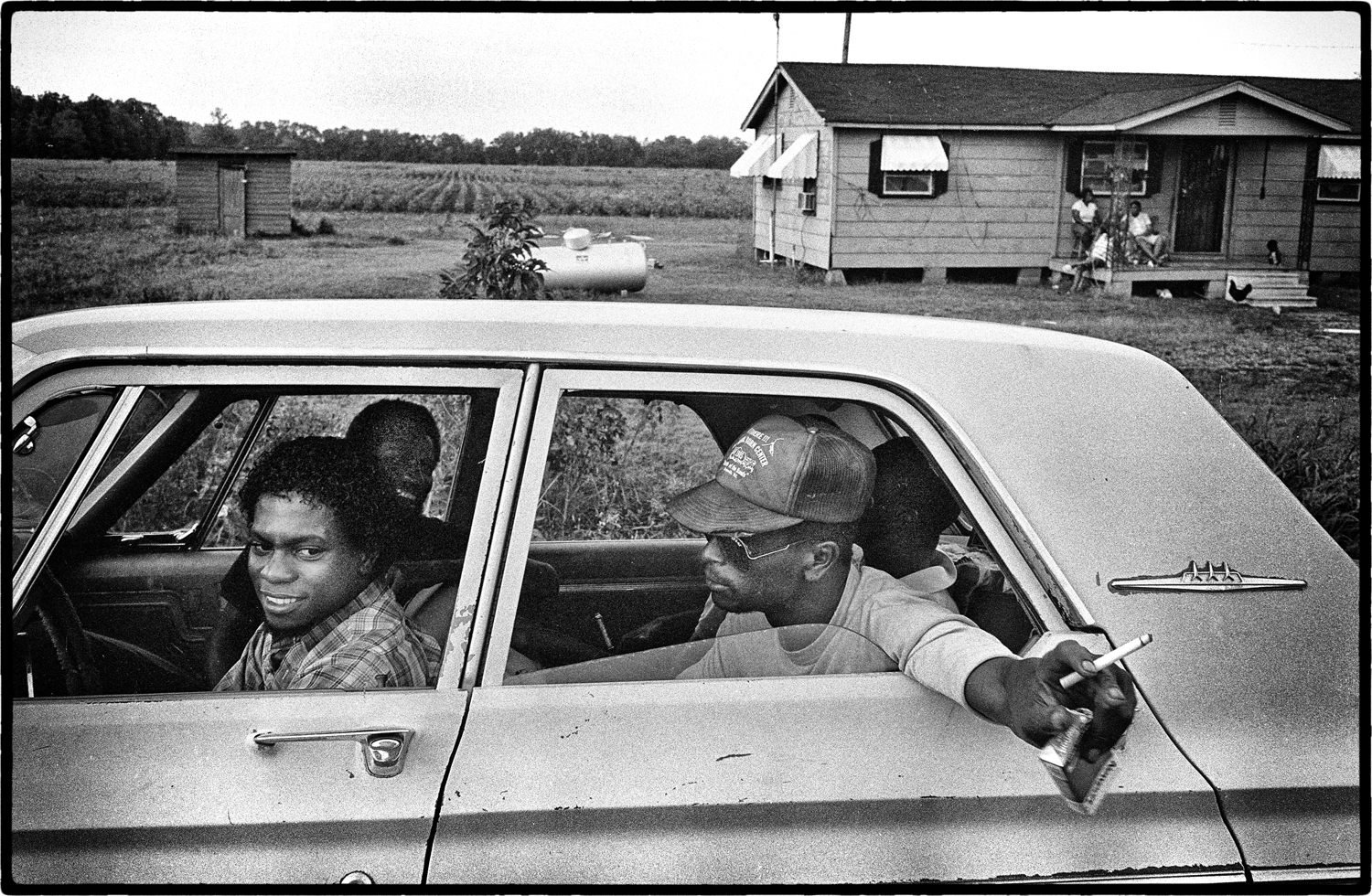

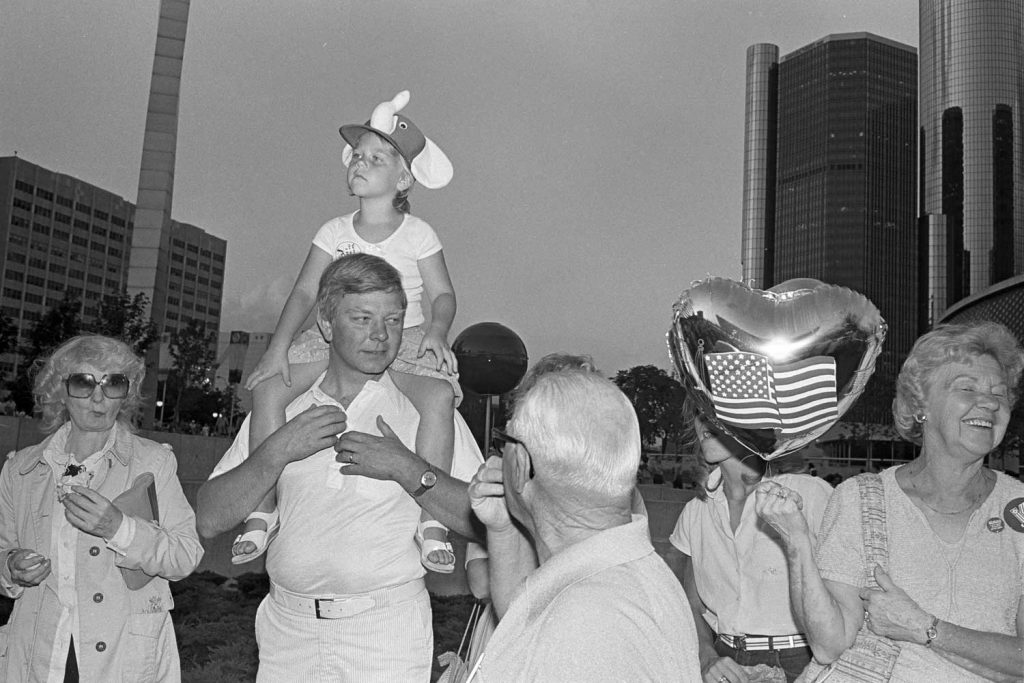

Detroit was once a prosperous city before its population started to decline in the 70’s. When I look at some of your photographs, I feel a « joie de vivre ». What was life in Detroit by the end of the 70’s and the beginning of the 80’s?

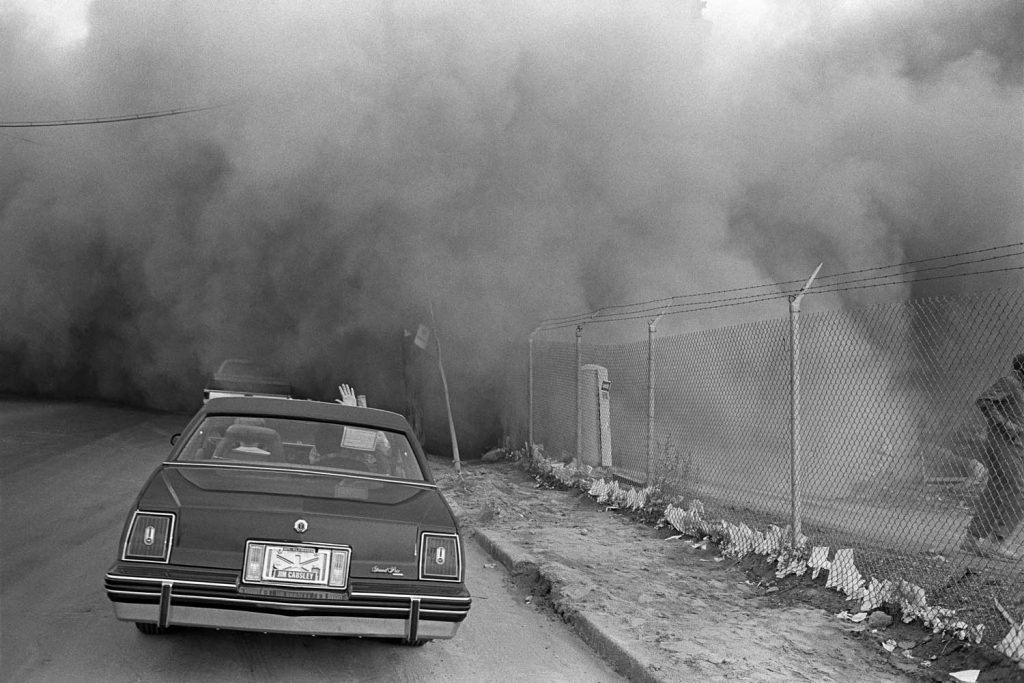

In the early 20th century Detroit was the «Silicon Valley» of its time. And arguably, when I was born there in 1950, Detroit was at its peak of prosperity and population, nearly 2 million people. During my lifetime it’s been a long and often desolate slide. The subject of Detroit’s decline is way above my pay grade and ability to elucidate though. Since coming of age photographically in the early seventies I’ve only lived one year (1973) in Detroit proper, and the rest of the time in Whitmore Lake, Ann Arbor, and South Lyon, all on the outskirts of the Detroit Metro area. The music of Detroit, automobiles, and driving, and the grittiness, and funkiness of its factories and people, all have been major influences on me and my attitudes toward living, but I was never much interested in photographing the grim and desperate elements of Detroit and its people. There certainly was a lot of that, even in the ‘70s and early ‘80s when I was making these pictures, but when I photographed, whether it was Detroit or the small towns around it, I was most interested in the social energy surrounding public events. So I think the « joie de vivre » you sense in the pictures comes from both that more narrow view and my joy in the act of photography. In other words, they’re not necessarily a very accurate representation of the times, I think. My truth I suppose. I can say that I had an awful lot of fun making them!

After so many years, how do you look at your photograph regarding the social context of the time?

Ha! It’s hard for even me to divorce myself from the present reality and put myself back in the world in which the pictures were made. But aside from not getting any younger part, I feel very fortunate to have lived a significant portion of my life in the pre-digital era. Age itself probably has a lot to do with it, but when I look at these photographs I remember a time in which people seemed less guarded in public and access to places without special permission was much easier. As an example, recently I went to photograph at my local high school football game and was questioned by the local police presence as to what I was doing. Essentially, I was told that I couldn’t photograph the students unless I made an appointment with the high school « media specialist » beforehand to be checked out and issued a special photographic permit. In 1980, without any credentials whatsoever, I could get within camera swinging distance of a presidential candidate and photograph at will.

In a previous interview, you mentioned Walker Evans, Russell Lee, Gary Winogrand, and Lee Friedlander. How did they influence your approach?

In ’72 –’74 I went to school to study photography. Before that, my photographic experience was mostly about the magic of the darkroom and messing around with my negatives and materials. At the school, I studied the history of photography for the first time. The FSA photographers, Walker Evans and Russel Lee in particular had a profound effect on me. Their straight matter-of-fact detailed descriptive pictures sold me on the power of the camera. Suddenly, it seemed obvious to me and deserving of respect. It must be dealt with, this power of the camera to describe. That fact shouldn’t/couldn’t be changed by me. And then Winogrand and Friedlander showed me that you could accept that respect for the camera image and use it to express your relationship with both the world as you found it and the evolving language of the photographic tribe. At that point, after two years at school, I could leave and figure out the rest as I went along.

« The music of Detroit, automobiles, and driving, the grittiness, and funkiness of its factories and people, all have been major influences on me and my attitudes towards living, but I was never much interested in photographing the grim and desporate elements of Detroit and its people. »

There is a true feel of honesty and spontaneity in your photographs whether it is your candid photographs, your portrait, or your landscape photographs. I am not going to ask you how you approach and take photographs of your subjects. I am more interested in your editing process. How do you edit your work? Do you have some criteria?

Quite honestly, this is an area where I feel inadequate. My pleasure comes from shooting and I tend not to want to go back over stuff I’ve already done. I’m more interested in the next opportunity to work with the camera down the road. I’m trying to work more on the editing process, but you know, sometimes one gets tired of looking at the same images over and over! I want new ones to look at! But actually, going through the process of making this book of archive pictures has been helpful to me. The black and white archive is finite, nothing more to add. I’ve got a pretty good grasp of the mid-seventies to early eighties period now and I am currently working on distilling it down to 20-25 images for a portfolio.

When did you stop using black & white film to shoot color film? Were there any reasons behind this change

Well, I never really shot much color film, except for the occasional roll of color transparency. My switch was from black and white film to digital color. I did this around 2005-6. I had built 5 darkrooms from 1968 to 1985, and when we moved to a new house in 2003 I wasn’t interested in building or working in a darkroom anymore. I had always wanted to work in color but balked at the cost of black and white. I have a strong practical streak and have been pretty much a minimalist when it comes to gear. So at that point, I figured I already had a computer, and it would be cheaper for me to sell my analog gear, get a DSLR, and set up a digital darkroom. So the reasons were both practical and a desire to change it up.

Does digital photography change your relationship with your camera and the way you approach photography compared to 40 years ago?

Ha! I have too much muscle memory with analog to have digital change me all that much. Even though shooting digital is supposedly « free » I don‘t find myself shooting a lot more images in a given situation. I couldn’t handle a big increase in volume! Essentially I still have the same relation to the camera image. What I look for in how the camera sees things, is what it can tell me about the scene. That hasn’t changed. Probably the biggest change, and one I like, is the ability to change sensitivity (ISO) on the fly. That’s liberating to me, without adding too much complexity. Also, being able to sync flash at a speed higher than 1/50sec is cool. Color is a big change for me, but digital just made it practical.

What is your top 5 desert Islands book?

If I look at my collection today and only had to keep five I would choose :

The Lines of My Hand, Robert Frank

First and Last, Walker Evans

American Prospects, Joel Sternfeld

Photographs, Lee Friedlander

Figments From the Real World, Garry Winogrand

Interview Jérome Lorieau / In Frame

Links: Don Hudson | Instagram