This project was a commission from The Guardian Weekend Magazine, we are interested in the working process so let’s start from the beginning. What is your organization before going to the field to take pictures?

First making sure my cameras and kit are all in working order, simple things like having extra batteries for example. Buy film and cards, sort visas, accommodation, notebooks, medical supplies. I focus on the basic practicalities of life – if these are done, then I can fully concentrate on the photography. I try to keep my clothes again to a minimum, good boots, jeans and cotton trousers, T-shirts and a jumper. I want to travel without anything non-essential.

Do you look for any contacts on the field? Do you make research before going?

It really depends if it’s a personal project I will both research and have contacts in the field, I will plan this all before maybe for a few months before so I have knowledge which is practical and current. If it is a commission then I will do both, independent research, speak to a journalist or writer also and if they or the commissioning party have contact in the field I will also contact them. Usually, with a commissioned piece with an NGO, these contacts are already in place.

Of course, that doesn’t mean that once you are in the field you don’t make new contacts, I think more often than not one person leads to another and that leads to more possibilities. With research I think it’s vital – written not visual – I am wary of looking at photographs taken by another photographer but at the same time it’s probably a good idea so you don’t replicate the locations on some projects.

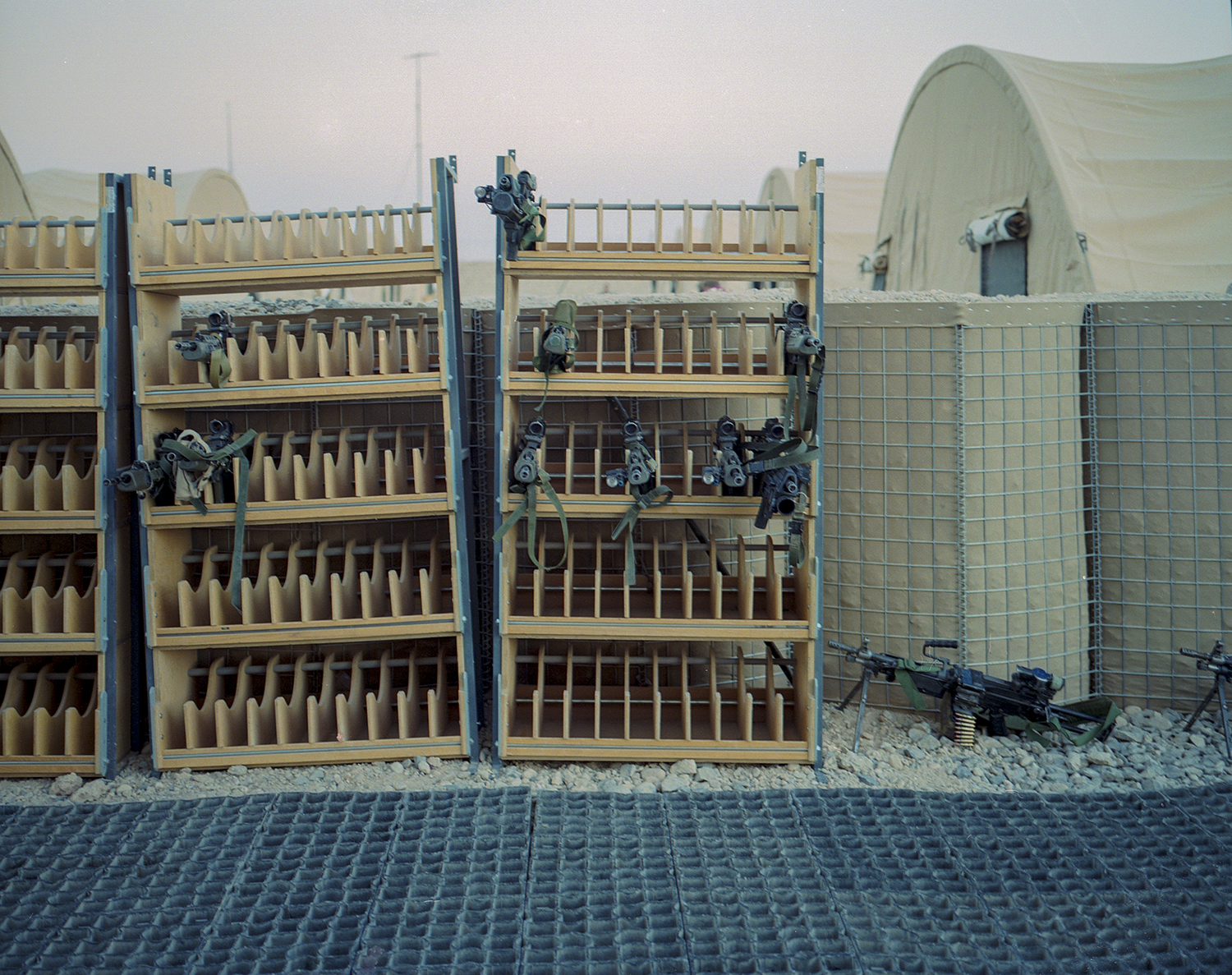

On this project, you seem to be working in an analog format. Was this your initial choice?

Yes I worked with a 2 Mamiya 7II with 65mm and 80mm, I think the film was Kodak Portra, but there may have been some Fuji I was carrying. The reason I used this camera is simply that I had worked with this camera on « Lost in the Wilderness » and The Guardian Weekend wanted the same authorship. I did also have a Canon DSLR with me which I used from time to time

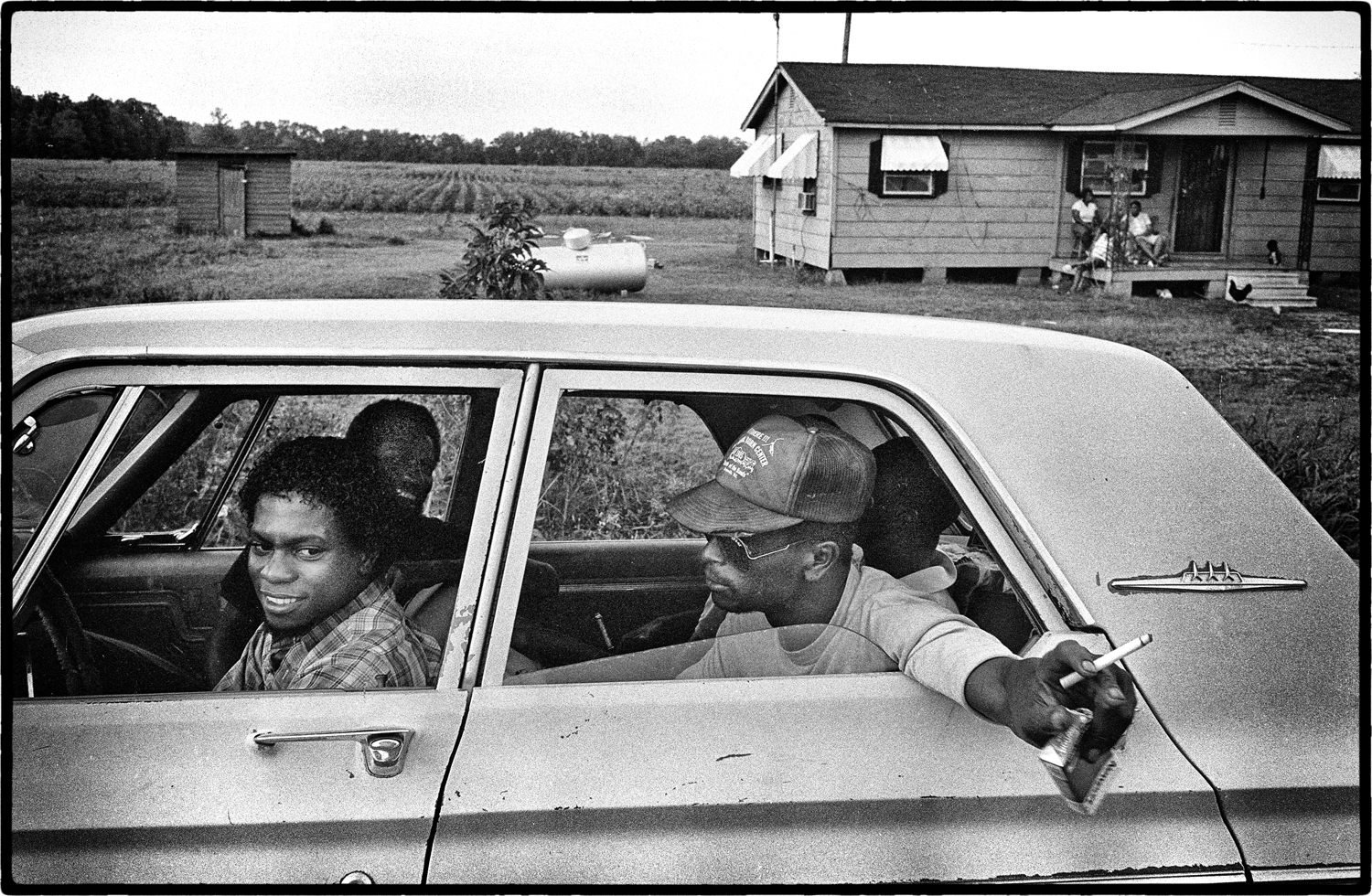

« What I didn’t want to make is photographing in the tradition of photojournalism »

The medium format is not as « flexible » as the 35mm format, the strength of your work is that the photos and your approach leave the necessary space to make our own story as viewers. You sometimes felt the need to change the format in parallel according to the moments?

The use of medium format was specifically because I wanted to be in control, the format has its positive limitations, that space you speak about is paramount to my practice. What I didn’t want to make is photographing in the tradition of photojournalism, the effects for example a wide-angle lens gives to composition – for me, that’s too easy too much 1,2,3 or dot to dot photography. A photograph for me has to breathe and let the viewer see through space.

I tried my best to always photograph with the medium format but of course, I understood that there were times with a situation would arise where it’s near impossible however all you can do is react and make what you can be used. For example the digital but also not react. I think firmly is that if you can psychological think of the digital format as an analog and also set rules for me singularly is not look at the back of the camera – not to pollute my mind – I don’t want to think I have made the photograph – one’s imagination and focus is destroyed. Discipline and Serendipity and Kismet.

How did it go for the first few days?

In all honesty, I was concerned at first – I am South Asian by heritage but was born in Forest Gate, East London. There was this duality in play – issues around racism in the army and also these ideas as a boy I wanted to be in the army. I can revert to my east London, cockney accent and, interestingly, after a few days the soldiers I feel didn’t see me as any other – the only time I can remember a look of surprise was when I was speaking to the Afghanis working in the camp is broken Urdu/ Hindi – I think the soldiers were taken back by that. My connection was fine with the soldiers I was living and walking with them every day. As a photographer, I am singular in my mindset I am there to make photographs and I navigated whatever or whoever I needed to do so.

« Acceptance comes from mutual respect as a human being. »

Did you get to know them easily?

Most of the soldiers were young men from the North of England and most simply, my upbringing in east London was much the same – working class. If we are to talk about a human connection I think the simplest is being there walking the same patrol, sleeping in the same tents, eating the same food. Acceptance comes from mutual respect as a human being. For me, that’s enough

Within a few days, not long, to be honest, I get along with most people – I think that once they knew I was there for the long run and once they had done their dance of poses and I still was hanging around making photographs. I think they understood that the photographs I wanted to make took time and patience. I think also clarity about why you are there.

Was there any kind of control from the army? How was the journey to get there?

There was a minder with me on patrols but no control in looking at or telling me not to take photographs etc I was pretty much free to do what I wanted. I think the only issue we had more was with the powers that be in terms of access to other F.O.B’s ( forward operating bases) where tabloid newspapers were given priority. We flew independently from the UK via the Middle East into Kabul and from Kabul then we started the embed process – that means in Kabul we were in barracks and then flew in Helmand on Army planes and helicopters. On the way home, we had to fly out on Military aircraft.

« I just felt I needed to take a step back and process the time I had there. »

When you came back, how was the editing process?

The good thing was there wasn’t a deadline – so I basically had the film processed and contacted and left it alone for a week. Whilst I wanted to see the work I just felt I needed to take a step back and process the time I had there. Once the editing started it involves me making a series of small prints and then editing tighter. I had to understand the photographs I made and more important why…

Once that is done it’s talking to the editor about this all. That doesn’t of course necessarily mean that the editor or designer is going to go with what you think. It’s a magazine …not a book or gallery where you the artist has control.

What are your photographic influences? at your beginnings and also today?

In the beginning, I was at the alter of Nachtwey, Salgado, Bresson, Capa, etc and I think that its important to say this as it was the beginning and I was a photojournalist at that time but I left that world and as I have explored photography the American movement of William Egglestone, Wiliam Christenberry, Stephen Shore, Mitch Epstein, Alec Soth have all had their influences Nigel Shafran, Stefan Ruiz, An My Le, Rineke Dijkstra, Paul Graham, Wolfgang Tillmans, Sohrab Hura, Clare Richardson I am drawn to very much I think if I was to say the one artist who has deeply affected me is Luc Delahaye. There is a clarity that demands you look at his photographs.

Your top 5 photobooks?

Very Difficult Question I am sure there are many from the above list of photographers who work always like to see in the books they make. But

Winterriese – Luc Delhaye

Dark Rooms – Nigel Shafran

Neu Welt – Wolfgang Tillmans

The Coast – Sohrab Hura

Beyond the Forest – Clare Richardson

Interview by Kalel Koven