Thank you for joining us today, Melinda. We’re excited to learn more about your remarkable work and the journey that led to it. To start, could you tell us what inspired you to travel to Brantville, New Brunswick, in 1972 and how it all began? Did you go specifically for a photography project?

In 1972, I was a first-year graduate student in Yale’s MFA Photography Program. I had already studied with Walker Evans as an undergraduate at Yale and, in the Fall of 1971, I helped curate Walker’s retrospective Walker Evans: Forty Years at the Yale Art Gallery. So many of Walker’s photographs resonated with me as we sifted through his archives, discussing and selecting photographs together. The large format, black and white photographs he made in 1936 in Hale County, Alabama inspired me as I was deciding where to make photographs in summer 1972. I bought a used 4×5 Deardorff view camera but, instead of traveling South as Walker did in 1936, I headed to a fishing village in Canada.

How were you initially connected with the Acadian fishing village and the fisherman’s family you lived with?

I joined the Quebec Labrador Foundation (QLF). QLF sent American students to organize and run day camps for the children in isolated fishing villages on the Eastern Shore of Canada from Labrador to New Brunswick. I was 1 of 5 students who spent the summer in Brantville, New Brunswick, a village of 1,000 French-speaking Acadians. I knew almost nothing about the history of the French Diaspora and the Acadian Peninsula but I was eager to see and make photographs there. I and two other women QLF student volunteers lived with a fisherman, Ulysse Thibodeau, his wife Jeannette, and their 3 young children. Like many of the men in Brantville and other villages on the Acadian Peninsula, Ulysse fished for lobster, cod, and mackerel during warm months and traveled to work in the lumber industry when it was too cold to fish.

How did you organize and structure your day camp activities to interact with the community and capture their lives? How did you secure funding, resources, and permissions?

QLF arranged for myself and the two other students to live with the Thibodeau. We shared their home, their family meals, and countless family activities, from birthday parties to picnics, with us. On our first morning at their house, Jeannette surprised us with lobsters for breakfast and sent us off to day camp every morning with a lunch of fried egg sandwiches. Camp days were filled with games like Duck Duck Goose and Capture the Flag, swimming lessons, art activities, and a final puppet show of Le Corbeau et Le Renard for parents and friends of campers. I got to know the people of Brantville but I only once, after the puppet show, made photographs at camp. When I wasn’t supervising camp activities, I had time to focus on the slow, deliberate process of setting up my view camera and making photographs. Almost all of my photographs were made inside or near the Thibodeaus’ house where we lived.

« They were fascinated watching me open the camera, disappear under my black cloth… »

Your work has a unique and emotional resonance. How did the people of Brantville react to you documenting their lives? Were they open to being photographed?

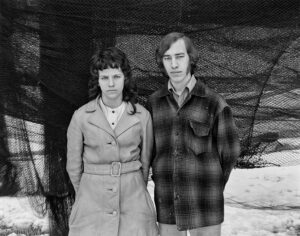

The Thibodeau family, their extended family, and friends were enthusiastic collaborators whenever I brought out my camera. The field next to our house was a constantly changing stage for making photographs. There were several small houses, a barn, often a car or truck or boat, bicycles, laundry, a rabbit hutch and pig pen, buoys, lobster traps, and, in winter fishing nets hanging on poles. I don’t remember anyone ever refusing to be photographed. On the contrary, children and adults, too, were happy to be photographed. A view camera was new to everyone and made the process special. They were fascinated watching me open the camera, disappear under my black cloth, and begin making adjustments to the camera but also giving them suggestions. Then I would come out from the black cloth, hold the shutter release, and watch closely. When I saw an expression or gesture or the light shift slightly, I tripped the shutter. I think it was a combination of wanting to help me and delighting in being seen.

Can you tell us more about your subsequent visits from 1972 to 1974? How did your relationship with the community evolve during this time? Did you go alone there or with your family? How long are you for each time? It was in summer?

I made 4 visits to Brantville. Two were in the summer of 1972 and again in 1974 when I went alone to stay with the Thibodeaus and make photographs for a month. The other two visits were between these summers, one in November and the other in March. It was cold both times and you could see snow and the harsh sunlight reflecting off the snow. That light was very different from the soft diffused light I often waited for in the summer.

Could you share more about the technical aspects of your photography? What considerations did you make in terms of framing, composition, and lighting while taking the portraits? Did you wait a long time before to see a print and see where you are in your project?

I used TriX film and reloaded film holders by going into a closet or the bathroom at night. I tried to make several exposures because I couldn’t see the negatives until I left Brantville and returned to process the film. I stored my Deardorff, tripod, and film holders under my cot. Remarkably, the young children never disturbed any of my equipment and my negatives were almost without exception fine when processed. Almost all the photographs are in natural light.

Can you discuss any particular challenges in getting your work recognized and published, and how did you overcome them?

A small number of my Brantville photographs were exhibited at Yale U Art Gallery in 1973 and a few were in an exhibit at the Addison Gallery of American Art in 1975. I began photographing more in color and on road trips in the US. It was not until Covid, isolated in the small fishing village where I live in RI, that I began to review and print my Brantville negatives, many of them for the first time. In 2022, I shared them with the Thibodeaus, still wonderful friends who feel like family, who were as excited as I was to see the series unfold. They are still my collaborators, now helping me remember the names and relationships of the people in the photographs. And I began to post Brantville photographs on Instagram a year ago.

Bill Shapiro, the former editor of LIFE magazine, saw my photographs on IG and made a post about my work on his own IG account. His IG has a large following and several publishers saw the work and reached out to ask me about making a book. Stanley Barker Books was one. I admired their books and accepted their offer to publish Brantville. I have learned a lot about bookmaking from Rachel and Gregory Barker and am excited that the book will be released this week.

When Nathalie, the younger Thibodeau daughter who is in a number of my photographs, saw the cover and endpapers of the book, she exclaimed “That’s perfect – it’s all about the water in Brantville!” I’m so delighted that the book reflects this special place. This little community is as welcoming and generous today as when they first greeted us with boiled lobsters for breakfast in 1972. When I finished printing the Brantville photographs, I wanted to exhibit them first in New Brunswick. Beaverbrook Art Gallery, the official museum of New Brunswick, reopened in 2022 after being closed for a 3-year expansion project. The Director, Thomas Smart, and the Curator, John Leroux, were excited to schedule an exhibit of 42 Brantville photographs. On April 1st. “Brantville: Melinda Blauvelt” opened. Despite a snowstorm, 40 friends from Brantville came to the Opening and, at the end of my Artist Talk, several of them came forward and offered their comments and memories of the photographs. It was a remarkable celebration of the photographs and this special community. Now I can’t wait to deliver copies of Brantville to my friends in Brantville! It’s now available and I’m going to enjoy taking it to Canada and Paris Photo and other places for the next few weeks!

« It is a privilege that the people in all these photographs allowed me to look so carefully and try again and again to capture something I couldn’t fully explain. »

Can you describe any specific moments or portraits that hold a special place in your heart, and what they represent to you?

Actually, I remember the excitement I felt when I was making almost every photograph. I’ve commented elsewhere, or others have, about several of the images. I’ll select a different one here – the portrait of “Eva with Chantal, Murielle & Her Doll”. This is the first photograph in the book. The simple houses, the boat, the triangle that is made by Eva tenderly embracing her daughters, each pair of eyes (even the eyes of the Patti PlayPal doll), the rhythm of the hands across the image, the dainty white flowers on Eva’s top and those scattered on the grass on the left, the white circles on Chantal’s dress and the circles of the nautical wheels on the doll’s dress, there are so many details to look at. I framed the photograph deliberately and Eva and the girls waited patiently, but none of us can plan the instant when each one has that particular expression and the elements combine to make a photograph that surprises and fascinates me. It is a privilege that the people in all these photographs allowed me to look so carefully and try again and again to capture something I couldn’t fully explain.

What are your top 5 photobooks?

There are so many! I’ll limit this to black and white. Here are 5 classic books I love:

American Photographs by Walker Evans

Many Are Called by Walker Evans

A Way of Seeing by Helen Levitt

The Americans by Robert Frank

The Decisive Moment by Henri Cartier-Bresson

Interview by Kalel Koven

Photographer’s Links: Website – Instagram

« Brantville » Book available now, get a copy – Published by Stanley Barker