Tell me when did you start this project and why?

I initially returned to Detroit in 2010 for the sole purpose of creating a re-photography project of several architectural buildings that I photographed in the early 1970s. I wanted to see what and how the buildings if they were still standing, had changed over a 37-year passage of time. Needless to say, there were many sad revelations as several buildings had laid waste or were completely torn down.

That project took me only a couple of weeks to complete as I had all of the addresses written on my old negative sleeves, so finding the locations was easy. That two-week stretch of time also gave me an introduction back into the city again since I moved from Detroit to Chicago in 1977 to start my career as a commercial photographer. Several photographers at the time had just published books on Detroit and all of their work related to Detroit’s dystopian, abandoned, architectural landscape.

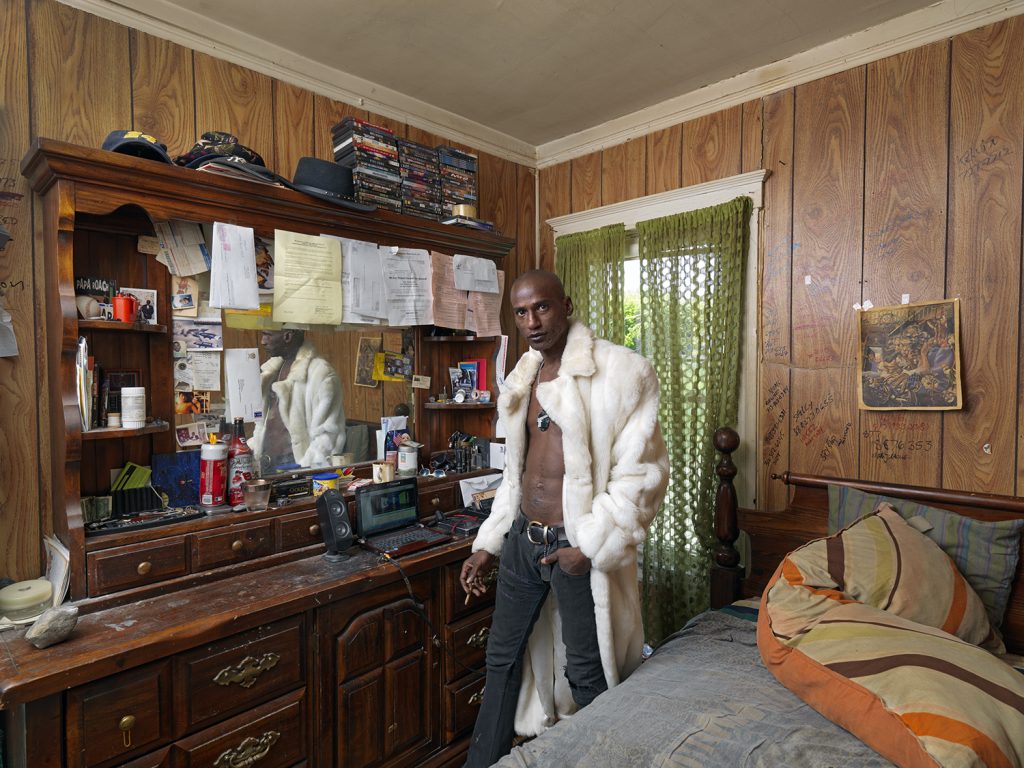

These photographs showed little, if any, of the human toll that Detroit’s ruination had inflicted on its citizens and I felt deeply troubled by their absence in these projects. After all, there were still 700,000 people living in Detroit after more than 1,100,000 people had left the city since the height of Detroit’s population in 1950 at 1,800,000.

So my focus turned to the neighborhoods in the city and the people who have struggled to survive and persevere in one of the poorest post-industrial cities in America that had fallen on hard times. I hoped that my work would make a connection between the viewer and those who I photographed in a way that created a level of understanding and human compassion.

« …I wanted to concentrate my time and tell a more human and connective story about those who have made a decision to rough it out and stay where they were, whether by choice or by economic reasons. »

Your work is over 5 years, right? (2010-2015)

Yes, from the beginning I knew this was going to be a long-term project, and I tend to work that way anyway. Detroit is 140 square miles and comprises a hundred different neighborhoods, but basically, the city is divided by its east and west side geography. Where I spent most of my time, whether on the east or west side, it was always in distressed neighborhoods, but if you look at the city logically, a major portion of it is distressed.

The cumulative effect leaves a city that is defined by neighborhoods that are linked socially, economically, and racially that all share a similar condition that you could describe as poverty struck. It’s here where I wanted to concentrate my time and tell a more human and connective story about those who have made a decision to rough it out and stay where they were, whether by choice or by economic reasons.

Your work is significant on how you get close to the different people?

It was imperative that this project included many portraits of residents living in the city to counter the perception Detroit was completely devoid of people, or at least prove that those who lived there shouldn’t be written off as nonexistent. I’ve never considered myself a portrait photographer per se but this project was based on the premise of creating a story about the human connection and that forced me to push myself and interact with people. Often times I would be setting up my camera and people within the area would watch me or even come over and ask me what I was doing.

« I never wanted to take advantage of someone’s situation and expressing my respect for them was a critical part of the project. »

This opened up a dialog where I could start a conversation and explain my project to them. Eventually, I would ask them if I could take their portrait and most people would say yes. From there, people would introduce me to their friends and family and the process would start anew again. I would visit many people over and over and as a thank you I would bring them a print from my previous trip.

It was a nice way of saying that I appreciated them for letting me into their lives. I never wanted to take advantage of someone’s situation and expressing my respect for them was a critical part of the project. These were people who were proud of who and where they came from in spite of their social and economic background.

How did you work for this project?

I didn’t pre-plan anything in the beginning. I just wanted to get to know the geographic areas of the city and reacquaint myself with the landscape. Detroit is approximately 140 square miles so there were days where I would use up an entire tank of gas just driving around. I’m sure I’ve amassed over 15,000 miles combined in all of my trips there. I still return to the same locations over and over as each trip can reveal new and different opportunities.

The last few years I’ve been documenting the city at night, making architectural views of everyday neighborhood commercial establishments and houses. That work has also been published in book form which came out in April of 2018, titled « A Detroit Nocturne », and even though the book has come out, I still continue to document the city at night. It’s become a very interesting addendum to the Detroit: Unbroken Down project in that it ties together the physical brick and motor structures of the city with the people who use them that provide a living for many of its residents.

Is there a story that touched you that you still remember?

The one person that I’ve stayed in contact with the most is a man named Tom. I met him in 2010 after reading a story about him in the Detroit Metro Times Magazine. After working several construction jobs as a carpenter and constantly getting laid off due to lack of work, he wound up homeless and living under a viaduct. Not wanting to deal with the uncertainty of working for someone else, he built himself a small shelter the size of a large doghouse on a plot of abandoned railroad property adjacent to the Detroit River.

He’s been living there independently now for over 12 years and in the interim has built two other larger structures. He has many supporters who bring him food and give him small donations, but by no means is he dependent on the goodness of others. He is completely self-reliant and has made a life for himself that transcends all of the hardships that he has faced. He is one of my most favorite and inspiring people I’ve ever met. I’ve photographed him on several occasions.

One other person I’ve met and photographed that made a huge impression on me was Nina. She was a double leg amputee after she was in a car accident 20 years ago that involved alcohol. She wouldn’t tell me much about the accident but she did reveal that she spent seven months recuperating in the hospital. She now lives in a house that her uncle bought for her through the Michigan Land Bank auction. The only furniture she has is a bed and a tv but she has running water, heat, and electricity.

She also has two dogs, Missy and Fluffygurl who pull her around in her wheelchair and take her to the store and to visit friends. She’s very tenacious, determined, and strong-willed and I found that this is very much a part of what you must do if you have to survive in Detroit. You can often see her with her dogs traveling down Houston-Whittier Street on the Eastside of the city.

What camera do you use? all digital?

Yes, I work digitally. I’ve been using the Hasselblad medium format H series digital cameras since 2004. I currently have the H6D-50c.

What is your influences in photography?

The complete history of photography from 1839 to the present has influenced me. You can’t be a serious photographer without that admission. It either gives us a path to follow or a reason to challenge long standing convictions and chart a new path. I’ve been a long time documentarian so my influences lie on the side of photographers who have upheld the belief that photography is a window to the world and less of a conceptual or abstract concept. Photographers such as Walker Evans, Eugene Atget, Steven Shore, Robert Addams, victoria sambunaris, Dawoud Bey, Emmit Gowin, Mitch Epstein, have all give me a foundation to work from.

Do you have a new project to come?

I’m continuing to expand my night photography beyond Detroit and have produced a new body of work in Chicago, and I’m also traveling south into the rural parts of Illinois again to add to my earlier Prairieland Project. I find the night photography to be challenging not only from a technical aspect but creatively as well.

Your top 5 photobooks?

Oh, there are so many, but I have to say that the top five books that I’ve purchased recently are at the top of my list.

– Seeing Deeply by Dawoud Bey

– Vanishing Vernacular, by Steve Fitch

– Diesel Fried Chicken, by Rob Hann

– Small Town Inertia, by J A Mortram

– The notion of Family, by Latoya Ruby Frazier

Interview by Kalel Koven